what was the main reason that europe began to trade opium for chinese goods?

The Opium Wars in the mid-19th century were a disquisitional juncture in mod Chinese history. The first Opium State of war was fought between Cathay and Cracking Britain from 1839 to 1842. In the second Opium War, from 1856 to 1860, a weakened China fought both Britain and French republic. China lost both wars. The terms of its defeat were a biting pill to eat: China had to cede the territory of Hong Kong to British control, open treaty ports to trade with foreigners, and grant special rights to foreigners operating inside the treaty ports. In addition, the Chinese government had to stand past as the British increased their opium sales to people in China. The British did this in the proper name of gratis trade and without regard to the consequences for the Chinese government and Chinese people.

The lesson that Chinese students learn today about the Opium Wars is that Communist china should never again let itself become weak, 'astern,' and vulnerable to other countries. Equally one British historian says, "If you talk to many Chinese about the Opium State of war, a phrase you lot will quickly hear is 'luo hou jiu yao ai da,' which literally means that if y'all are astern, you will take a chirapsia."one

Two Worlds Collide: The Starting time Opium War

In the mid-19th century, western imperial powers such as Britain, France, and the U.s. were aggressively expanding their influence around the world through their economic and military strength and by spreading religion, mostly through the activities of Christian missionaries. These countries embraced the idea of free trade, and their militaries had become so powerful that they could impose such ideas on others. In one sense, China was relatively effective in responding to this foreign encroachment; unlike its neighbours, including nowadays-day India, Burma (now Myanmar), Malaya (at present Malaysia), Indonesia, and Vietnam, China did non become a total-fledged, formal colony of the West. In add-on, Confucianism, the system of beliefs that shaped and organized China's civilization, politics, and society for centuries, was secular (that is, not based on a religion or belief in a god) and therefore was not necessarily an obstacle to science and modernity in the ways that Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism sometimes were in other parts of the world.

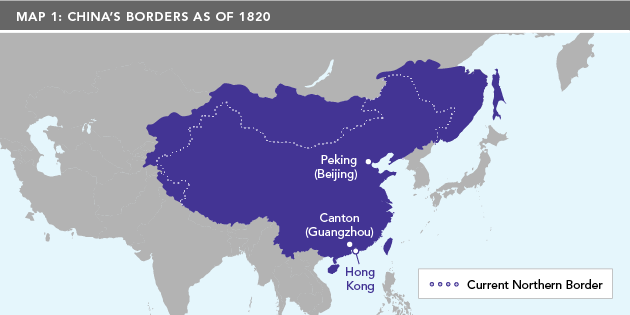

But in another sense, China was non effective in responding to the "modernistic" West with its growing industrialism, mercantilism, and armed forces strength. Nineteenth-century Communist china was a large, mostly state-based empire (see Map ane), administered by a c. 2,000-twelvemonth-former bureaucracy and dominated by centuries one-time and conservative Confucian ideas of political, social, and economical management. All of these things fabricated China, in some ways, dramatically dissimilar from the European powers of the mean solar day, and it struggled to bargain effectively with their encroachment. This ineffectiveness resulted in, or at least added to, longer-term problems for China, such equally unequal treaties (which volition be described later on), repeated foreign military invasions, massive internal rebellions, internal political fights, and social upheaval. While the first Opium War of 1839–42 did not crusade the eventual collapse of Red china'due south 5,000-twelvemonth imperial dynastic system seven decades later, it did help shift the balance of power in Asia in favour of the West.

Map 1: China'south Borders every bit of 1820.

Map 1: China'south Borders every bit of 1820.

Opium and the West's Encompass of Costless Trade

In the decades leading upwardly to the get-go Opium War, trade between China and the Due west took identify inside the confines of the Canton Organisation, based in the southern Chinese urban center of Guangzhou (besides referred to every bit Canton). An earlier version of this system had been put in identify past Mainland china nether the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), and farther developed by its replacement, the Qing Dynasty, as well known as the Manchu Dynasty. (The Manchus were the ethnic grouping that ruled China during the Qing period.) In the year 1757, the Qing emperor ordered that Guangzhou/County would be the only Chinese port that would be opened to merchandise with foreigners, and that merchandise could take place but through licensed Chinese merchants. This finer restricted strange trade and subjected it to regulations imposed by the Chinese government.

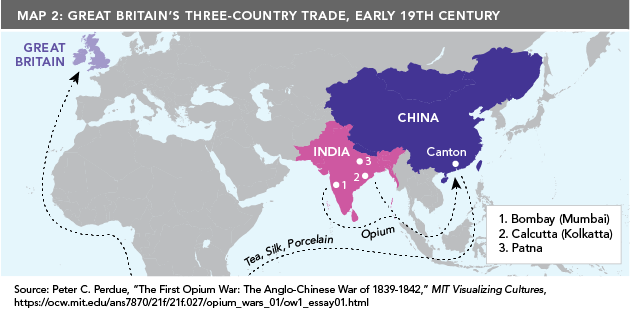

For many years, Uk worked within this system to run a iii country trade operation: Information technology shipped Indian cotton and British silver to Cathay, and Chinese tea and other Chinese goods to United kingdom (meet Map 2). In the 18th and early 19th centuries, the residuum of merchandise was heavily in China's favour. 1 major reason was that British consumers had adult a stiff liking for Chinese tea, too every bit other goods like porcelain and silk. But Chinese consumers had no similar preference for any goods produced in Britain. Because of this merchandise imbalance, Britain increasingly had to use silverish to pay for its expanding purchases of Chinese goods. In the belatedly 1700s, U.k. tried to alter this balance past replacing cotton with opium, also grown in Republic of india. In economic terms, this was a success for Britain; by the 1820s, the rest of trade was reversed in Britain'southward favour, and it was the Chinese who now had to pay with silverish.

Map 2: Britain'due south Iii-Country Merchandise, Early 19th Century.

Map 2: Britain'due south Iii-Country Merchandise, Early 19th Century.

Figure ane: A "stacking room" in an opium factory in Patna, Bharat. On the shelves are balls of opium that were part of Uk's trade with China.

The Scourge and Profit of Opium

The opium that the British sold in China was made from the sap of poppy plants, and had been used for medicinal and sometimes recreational purposes in Cathay and other parts of Eurasia for centuries. After the British colonized large parts of India in the 17th century, the British East Republic of india Company, which was created to take advantage of merchandise with Eastern asia and India, invested heavily in growing and processing opium, especially in the eastern Indian province of Bengal. In fact, the British developed a profitable monopoly over the cultivation of opium that would be shipped to and sold in China.

By the early 19th century, more and more Chinese were smoking British opium as a recreational drug. But for many, what started as recreation presently became a punishing habit: many people who stopped ingesting opium suffered chills, nausea, and cramps, and sometimes died from withdrawal. In one case fond, people would often do virtually anything to continue to go access to the drug. The Chinese government recognized that opium was becoming a serious social trouble and, in the year 1800, information technology banned both the product and the importation of opium. In 1813, it went a stride farther by outlawing the smoking of opium and imposing a punishment of beating offenders 100 times.

Figure two: Opium smoking in Prc.

Figure two: Opium smoking in Prc.

In response, the British Due east India Company hired private British and American traders to transport the drug to China. Chinese smugglers bought the opium from British and American ships anchored off the Guangzhou coast and distributed it inside Communist china through a network of Chinese middlemen. By 1830, there were more than 100 Chinese smugglers' boats working the opium trade.

This reached a crisis point when, in 1834, the British East India Company lost its monopoly over British opium. To compete for customers, dealers lowered their selling toll, which made information technology easier for more people in Prc to buy opium, thus spreading further use and add-on.

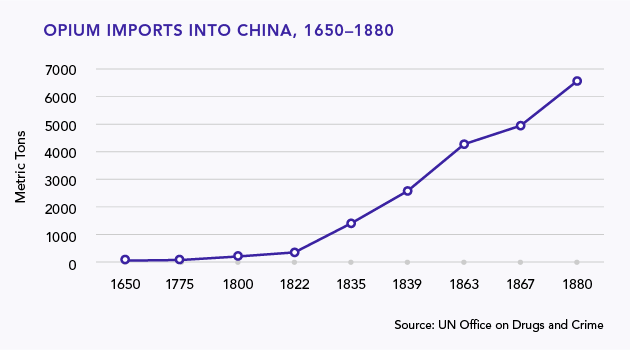

In less than 30 years—from 1810 to 1838—opium imports to Prc increased from 4,500 chests (the large containers used to send the drug) to forty,000. Every bit Chinese consumed more and more than imported opium, the outflow of silver to pay for it increased, from about two million ounces in the early 1820s to over nine million ounces a decade later on. In 1831, the Chinese emperor, already aroused that opium traders were breaking local laws and increasing addiction and smuggling, discovered that members of his ground forces and regime (and even students) were engaged in smoking opium.

The Users Versus Pushers Debate

Past 1836, the Chinese government began to go more serious about enforcing the 1813 ban. It airtight opium dens and executed Chinese dealers. But the trouble only grew worse. The emperor chosen for a debate amongst Chinese officials on how best to bargain with the crisis. Opinion were polarized into two sides.

1 side took a pragmatic approach (that is, an approach not focused on the morality of the outcome). It focused on targeting opium users rather than opium producers. They argued that the production and sale of opium should be legalized and then taxed past the government. Their belief was that taxing the drug would make it so expensive that people would accept to fume less of it or not fume information technology at all. They also argued that the money collected from taxing the opium trade could help the Chinese government reduce acquirement shortfalls and the outflow of silver.

Another side vehemently disagreed with this 'pragmatic' approach. Led by Lin Zexu, a very capable and ambitious Chinese authorities official, they argued that the opium trade was a moral issue, and an "evil" that had to be eliminated by whatever ways possible. If they could not suppress the trade of opium and addiction to it, the Chinese empire would accept no peasants to piece of work the land, no townsfolk to pay taxes, no students to report, and no soldiers to fight. They argued that instead of targeting opium users, they should terminate and punish the "pushers" who imported and sold the drug in Cathay.

Effigy 3: Lin Zexu.

Effigy 3: Lin Zexu.

In the end, Lin Zexu'due south side won the statement. In 1839, he arrived in Guangzhou (County) to supervise the ban on the opium trade and to crack downward on its use. He attacked the opium merchandise on several levels. For example, he wrote an open letter to Queen Victoria questioning Britain'southward political support for the trade and the morality of pushing drugs. More importantly, he made rapid progress in enforcing the 1813 ban by arresting over 1,600 Chinese dealers and seizing and destroying tens of thousands of opium pipes. He too demanded that foreign companies (British companies, in item) turn over their supplies of opium in exchange for tea. When the British refused to exercise and then, Lin stopped all foreign trade and quarantined the area to which these foreign merchants were bars.

After six weeks, the foreign merchants gave in to Lin's demands and turned over 2.6 million pounds of opium (over 20,000 chests). Lin'due south troops also seized and destroyed the opium that was being held on British ships—the British superintendent claimed these ships were in international waters, only Lin claimed they were anchored in and around Chinese islands. Lin then hired 500 Chinese men to destroy the opium by mixing information technology with lime and common salt and dumping information technology into the bay. Finally, he pressured the Portuguese, who had a colony in nearby Macao, to expel the uncooperative British, forcing them to motility to the island of Hong Kong.

Effigy 4: British officers in their tent during the commencement Opium War, circa 1839.

Effigy 4: British officers in their tent during the commencement Opium War, circa 1839.

Taken together, these actions raised the tensions that led to the outbreak of the showtime Opium War. For the British, Lin's destruction of the opium was an barb to British dignity and their concepts of trade. Many British merchants, smugglers, and the British East Bharat Company had argued for years that China was out of impact with "civilized" nations, which practised complimentary trade and maintained "normal" international relations through consular officials and treaties. More to the indicate, British representatives in Guangzhou requested that merchants plow over their opium to Lin, guaranteeing that the British authorities would recoup them for their losses. The idea was that in the short term, this would prevent a major conflict, and that information technology would go along the merchants and transport captains safe while reopening the extremely assisting China merchandise in other appurtenances. The huge opium liability (the opium was worth millions of pounds sterling), and increasingly shrill demands from merchants in China, India, and London when they discovered their profits were destroyed, gave politicians in Great Britain the alibi they were looking for to act more forcefully to aggrandize British imperial interests in Communist china. State of war bankrupt out in November 1839 when Chinese warships clashed with British merchantmen.

Effigy 5: Chinese swordsman, 1844.

Effigy 5: Chinese swordsman, 1844.

In June 1840, 16 British warships and merchantmen—many leased from the primary British opium producer, Jardine Matheson & Co.—arrived at Guangzhou. Over the next two years, the British forces bombarded forts, fought battles, seized cities, and attempted negotiations. A preliminary settlement called for China to sacrifice Hong Kong to the British Empire, pay an indemnity, and grant U.k. full diplomatic relations. Information technology also led to the Qing government sending Lin Zexu into exile. Chinese troops, using antiquated guns and cannons, and with limited naval ships, were largely ineffective confronting the British. Dozens of Chinese officers committed suicide when they could not repel the British marines, steamships, and merchantmen.

Figure 6: The British battery of Guangzhou/Canton.

Figure 6: The British battery of Guangzhou/Canton.

The State of war's Aftermath

The starting time Opium State of war ended in 1842, when Chinese officials signed, at gunpoint, the Treaty of Nanjing. The treaty provided extraordinary benefits to the British, including:

- an excellent deep-h2o port at Hong Kong;

- a huge indemnity (compensation) to be paid to the British authorities and merchants;

- v new Chinese treaty ports at Guangzhou (County), Shanghai, Xiamen (Amoy), Ningbo, and Fuzhou, where British merchants and their families could reside;

- extraterritoriality for British citizens residing in these treaty ports, pregnant that they were subject to British, not Chinese, laws; and

- a "most favoured nation" clause that whatsoever rights gained by other foreign countries would automatically apply to Great Great britain as well.

For China, the Treaty of Nanjing provided no benefits. In fact, Chinese imports of opium rose to a peak of 87,000 chests in 1879 (come across Figure 1). After that, imports of opium declined, then ended during the First World War, as opium production within China outgrew foreign production. Nonetheless, other trade did not expand as much every bit foreign merchants had hoped, and they continued to arraign the Chinese government for this. Among Chinese officials, the aftermath of the state of war led to a bitter political struggle between ii factions: a peace faction, which was roughly aligned with the 'users' faction in the opium trade argue; and a 'war' faction, which was roughly aligned with the 'pushers' faction in that fence. The peace faction was in nominal control.

Effigy 7: Opium War Imports into Prc, 1650-1880.

Effigy 7: Opium War Imports into Prc, 1650-1880.

In addition, the Treaty of Nanjing ended the County System that had been in place since the 17th century. This was followed in 1844 by a system of unequal treaties between China and western powers. Through the most favoured nation clauses, these treaties immune westerners to build churches and spread Christianity in the treaty ports. Western imperialism and free merchandise had its start great victory in China with this war and its resulting treaties.

When the Chinese emperor died in 1850, his successor dismissed the peace faction in favour of those who had supported Lin Zexu. The new emperor tried to bring Lin dorsum from exile, simply Lin died along the way. The Chinese court kept finding excuses not to accept foreign diplomats at the capital city of Beijing, and its compliance with the treaties fell far short of western countries' expectations.

2d Opium State of war (1856–1860)

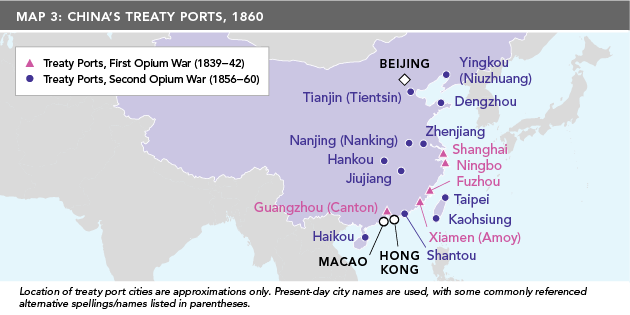

In 1856, a 2nd Opium War broke out and continued until 1860, when the British and French captured Beijing and forced on China a new round of diff treaties, indemnities, and the opening of xi more treaty ports (see Map three). This also led to increased Christian missionary work and legalization of the opium merchandise.

Map 3: China'due south Treaty Ports, 1860.

Map 3: China'due south Treaty Ports, 1860.

Fifty-fifty though new ports were opened to British merchants later on the offset Opium State of war, the Chinese dragged their feet on implementing the agreements, and legal trade with People's republic of china remained limited. British merchants pressed their regime to practice more, but the government's hands were tied because the Chinese government in the upper-case letter city of Beijing restricted who it met with.

In October 1856, Chinese authorities arrested the Chinese crew of a ship operated by the British. The British used this every bit an opportunity to pressure China militarily to open up itself upwards even farther to British merchants and trade. France, using the execution in People's republic of china of a French Christian missionary as an excuse, joined the British in the fight. Joint French-British forces captured Guangzhou before moving n to the urban center of Tianjin (also referred to as Tientsin). In 1858, the Chinese agreed—on paper—to a series of western demands contained in documents like the Treaty of Tientsin. But then they refused to ratify the treaties, which led to further hostilities.

In 1860, British and French troops landed near Beijing and fought their mode into the city. Negotiations quickly broke downwards and the British Loftier Commissioner to Cathay ordered the troops to loot and destroy the Imperial Summertime Palace, a circuitous and garden where Qing Dynasty emperors had traditionally handled the country'due south official matters.

Before long later that, the Chinese emperor fled to Manchuria in northeast Prc. His brother negotiated the Convention of Beijing, which, in addition to ratifying the Treaty of Tientsin, added indemnities and ceded to Uk the Kowloon Peninsula across the strait from Hong Kong. The state of war ended with a greatly weakened Qing Dynasty that was now confronted with the need to rethink its relations with the outside globe and to modernize its military, political, and economical structures.

Thinking Near the Opium State of war

In 1839, the British imposed on China their version of free merchandise and insisted on the legal right of their citizens (that is, British citizens) to do what they wanted, wherever they wanted. Chinese critics point out that while the British made lofty arguments about the 'principle' of free trade and individual rights, they were in fact pushing a product (opium) that was illegal in their own state.

There are different viewpoints on what was the main underlying factor in Britain's involvement in the Opium Wars. Some in the west claim that the Opium Wars were most upholding the principle of costless trade. Others, yet, say that Great britain was acting more in the interest of protecting its international reputation while it was facing challenges in other parts of the globe, such as the Nearly East, India, and Latin America. Some American historians have argued that these conflicts were not and then much most opium every bit they were well-nigh western powers' desire to expand commercial relations more broadly and to do away with the County trading system. Finally, some western historians say the state of war was fought at to the lowest degree partly to keep China'south residue of trade in a deficit, and that opium was an constructive style to do that, even though it had very negative impacts on Chinese order.

It is important to point out that not everyone in Great britain supported the opium merchandise in China. In fact, members of the British public and media, every bit well every bit the American public and media, expressed outrage over their countries' support for the opium trade.2

From China'south historical perspective, the first Opium War was the beginning of the end of late Imperial Communist china, a powerful dynastic organization and advanced civilization that had lasted thousands of years. The war was besides the commencement salvo in what is now referred to in China as the "century of humiliation." This humiliation took many forms. China's defeat in both wars was a sign that the Chinese land's legitimacy and ability to project power were weakening. The Opium Wars further contributed to this weakening. The unequal treaties that western powers imposed on China undermined the means Communist china had conducted relations with other countries and its trade in tea. The continuation of the opium trade, moreover, added to the cost to China in both silverish and in the serious social consequences of opium habit. Furthermore, the many rebellions that broke out within China after the first Opium War made it increasingly difficult for the Chinese government to pay its taxation and huge indemnity obligations.

Present-day Chinese historians run across the Opium Wars as a wars of assailment that led to the hard lesson that "if you are 'backward,' you will have a beating." These lessons shaped the rationale for the Chinese Revolution against imperialism and feudalism that emerged, so succeeded, decades later.

About the Author

Jack Patrick Hayes, PhD, is a professor of Chinese and Japanese history at Kwantlen Polytechnic University in Vancouver. His enquiry focuses on late imperial and mod Chinese and Tibetan environmental history, resource development, and ethnic relations in western China.

End Notes:

1 Andrew Moody, "Lessons of the Opium State of war," China Daily, Feb 24, 2012, http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/weekly/2012-02/24/content_14681839.htm.

2 See, for instance, Peter Perdue, "The First Opium War: The Anglo-Chinese War of 1839-1842," MIT Visualizing Cultures, p. 29, https://ocw.mit.edu/ans7870/21f/21f.027/opium_wars_01/ow1_essay01.html.

livingstoncortild.blogspot.com

Source: https://asiapacificcurriculum.ca/learning-module/opium-wars-china

0 Response to "what was the main reason that europe began to trade opium for chinese goods?"

Post a Comment